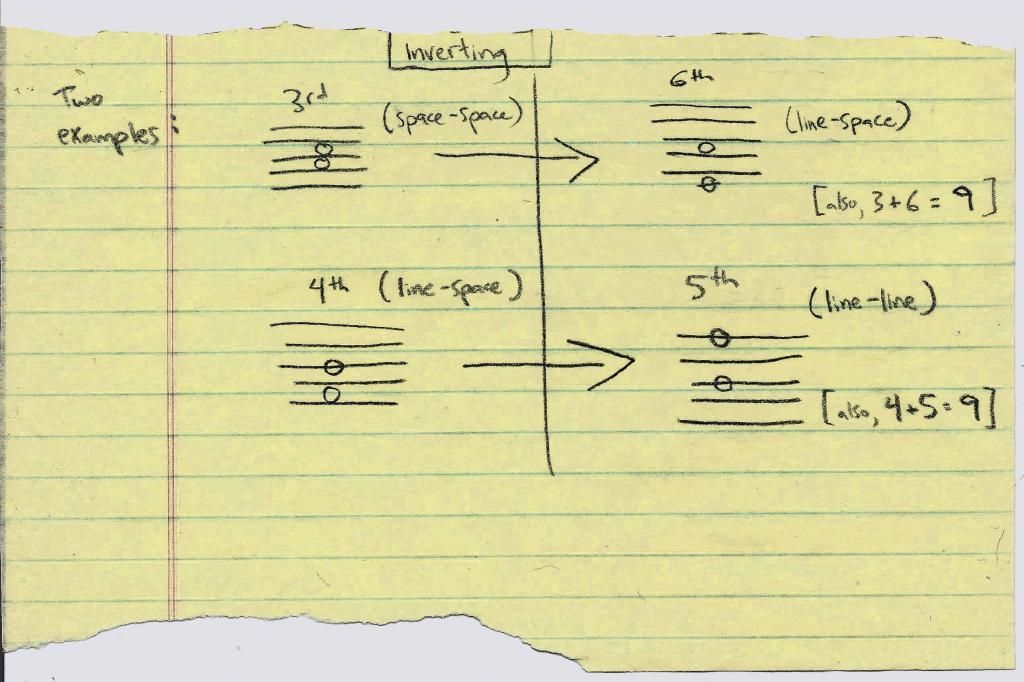

When I teach beginner-level piano students, one of the first things they learn is the "step" vs. "skip" concept. This coincides with their introduction to reading music from a staff. If a "line" note goes up to the adjacent "space" note, we call it a step (like stepping up on a flight of stairs). But if that line note goes up to a note on the next line above, we call it a skip (it is skipping the space between the lines). This is often how students begin their understanding of

intervals. They soon learn that the line-space example is called a 2nd, and the line-line example is a 3rd.

Beyond 2nds and 3rds, of course, the intervals become larger, and perhaps can be a little trickier to identify on a staff. Fortunately, with a little practice, this becomes easier and easier, until soon enough it is second-nature.

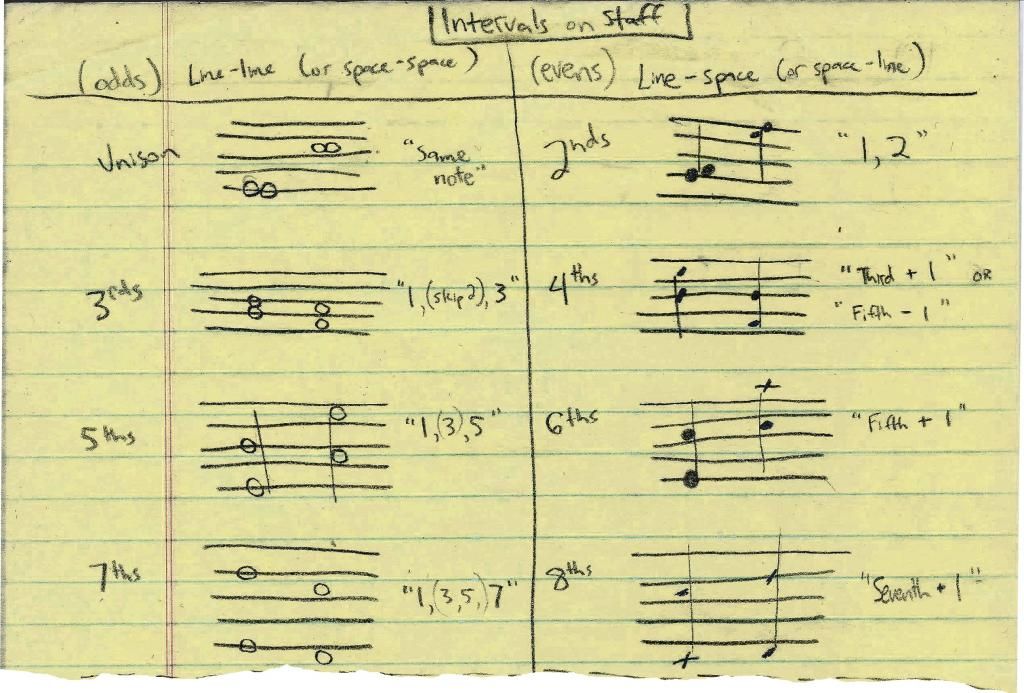

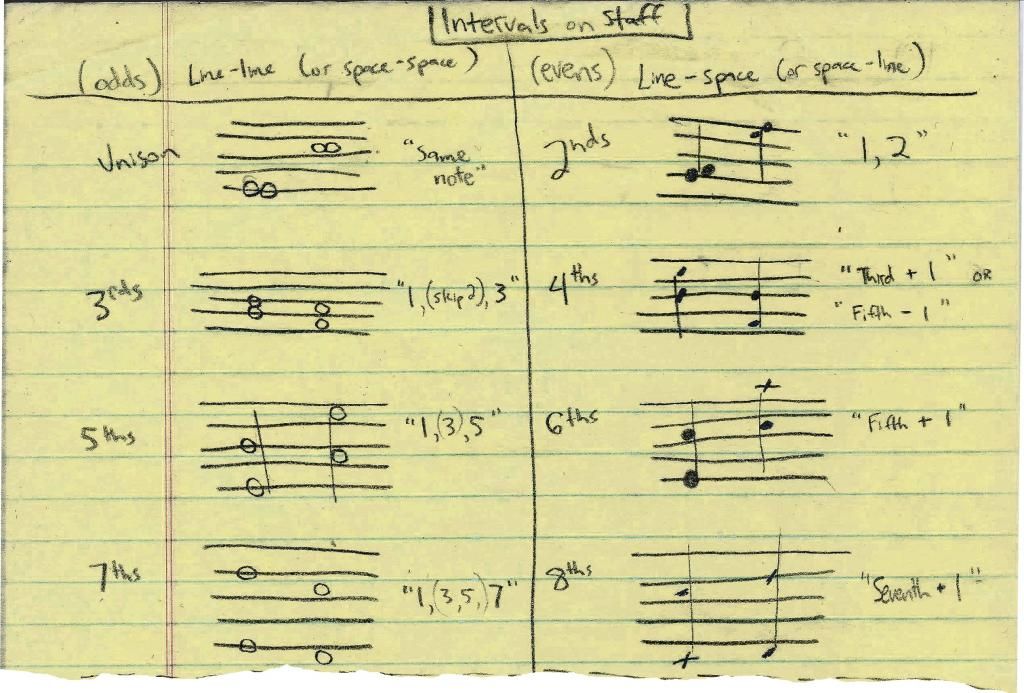

Here's a handwritten sheet showing what different

intervals (unisons up to octaves) look like on the staff (5 lines, 4 spaces) The ability to quickly recognize an interval (and eventually, several intervals/chords at once) when reading from written music notation--especially when sight-reading--is very valuable.

|

| I hope my handwriting is legible for you. Click to enlarge. |

In quotation marks, I wrote out simple mental steps someone might go through when looking at each interval. Visually, when I see a 7th, I like to imagine climbing up the rungs of a ladder (i.e. going from one line to the line above). On each rung, I can count up by odd numbers: "1, 3, 5,

7." A four-line ladder means I'm looking at a 7th.

The basic nugget of information to take-away from this post is this:

Intervals of Odd Numbers (1, 3, 5, 7) always appear as line-line or space-space.

Intervals of Even Numbers (2, 4, 6, 8) always appear as line-space or space-line.

To help visualize these intervals in another way (pianists especially), it would be a good idea to plunk out each of the intervals depicted above on a keyboard. Begin doing this in the key of C major (all white keys), and when comfortable try out some other keys in order to incorporate black keys into your visual memory bank.